Authenticating Your IdentityWhile you use your computer, a number of applications will need to know who you are. Authentication is the name of the process that lets you prove your identity to the computer system. You regularly use authentication, even when you are not using your computer. When you call someone using a phone, the person you call responds by answering the phone. You, in turn, let the person know who's calling, and, hopefully, the person you called recognizes your name and voice, thereby authenticating you.

You've already seen several examples of authentication in Mac OS X: login window, Mail, and the Connect to Server window in the Finder. Each of these applications needs to know your identity so that you can access some resource. In the case of the login window, your identity is needed to verify that you have an account: either on the computer you are logging in to, or on a server if your computer is configured for network user accounts. If you have an account, you are then given access to the Finder and all of your files. Often, it is some other computer on the network that needs to know who you are. The mail server may need to know your identity in order to know which mailbox holds your messages. The AFP server needs to know your identity to know which volumes you can mount and which files you can access. NOTE Authentication is not the same as authorization. Authentication is simply identification of a person. Authorization is what services or data you are allowed to access based on who you are authenticated as. In the case of the phone call, you were authenticated when the person recognized your name and voice. Whether or not the person continues to talk to you is authorization. Typically one thinks of authentication as entering a user name and password. While that is usually the first step, authentication also includes how a service verifies the information. There are several authentication methods. Which ones are available depends upon the client application and service protocols being used.

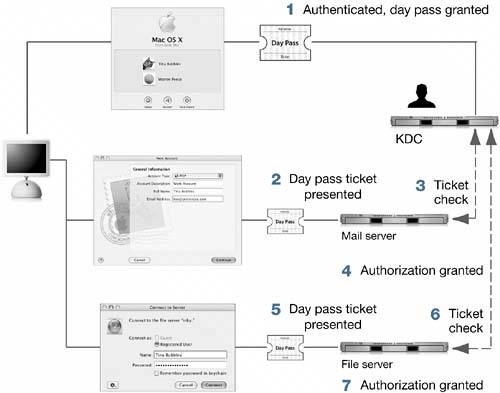

NOTE Mac OS X supports third-party User Authentication Mechanism (UAM) plug-ins to control access to file servers. To use a UAM, place the UAM plug-in in /Library/Filesystems/AppleShare/Authentication. Mac OS X supports natively written UAMs from Microsoft. The Microsoft UAM allows you to use long and encrypted passwords when logging in to a Windows server running AFP services. While running Classic applications, you can continue to use the UAMs written for Mac OS 9. Authenticating Using Basic/ClearTextThe simplest form of authentication is Basic, also known as ClearText because the client application sends the user name and password in an unencrypted form to the server. Basic authentication is not secure because anyone on the network can monitor network traffic and spot the passwords. Basic authentication should only be used on a private, secure network. Authenticating Using an Encrypted PasswordThis is similar to ClearText authentication, except the application sends the password in an encrypted form. This is more secure than basic authentication, but still not completely secure, as someone monitoring the network traffic can eventually decrypt the password. A more secure method is for the server to send the client computer a random number or string. The client computer encrypts the string using the password and sends the result back to the server. Meanwhile, the server also encrypts the same string with its copy of the user's password. When the server receives the encrypted string from the client, the server compares the client's encrypted string with the string it created. If the two strings match, the user is authenticated. This is more secure because the user password is never sent across the network. Also, because the initial string that the server sends can change, someone monitoring the traffic can't later recreate the response. Authenticating Using TicketsYou can see how user names and passwords quickly proliferate. Imagine if you needed to access a dozen different serversyou might have a dozen different passwords. Even if you had the same name and password on every one of them, when you change your password, you would have to change it twelve times if you wanted to keep all of your passwords the same. Keychain in Mac OS X is one way to address this issue. Keychain keeps your many passwords in a secure file format. Depending on your site, Keychain may be your only way to address the multiple password issue, because the other solutions rely on changes in the configuration of servers on the network that you may not control. Another way to deal with the problem of multiple login accounts is through the use of tickets. Rather than proving your identity to network services by presenting a user name and password, you prove your identity by presenting a piece of data (the ticket). The service verifies your ticket, and if the ticket is valid, you are granted access. The name of the system that implements this ticket architecture is Kerberos. A directory service solves the multiple account problem by coordinating all of its associated servers to use a single list of users. Kerberos simplifies this by keeping the list of users on one computer only. The ticket mechanism ensures that the rest of the services don't need your name and password; they only need a valid ticket. With Kerberos, you negotiate with one system on the network, called a Key Distribution Center (KDC). When the KDC is satisfied that you have authenticated (typically by entering the correct user name and password), it gives you the ticket required to access other servers on the network. In Mac OS X, this is integrated with the login window, so the initial login results in the user obtaining a ticket that can be used for the duration of the login session.

A ticket is a piece of data. Tickets are encoded in such a way that each one is unique. Each service can inspect the ticket and verify that the ticket is valid. To prove your identity to a server, you send your ticket instead of sending a name and password. Because the user's password is never sent across the network, it can't be stolen by someone monitoring the network. A ticket is not something an end user normally works with directly. If the system is set up and working correctly, a user's system will acquire tickets and present them when required to access a server, all in the background. A Kerberos system, when properly configured, is not only very secure but it is also very user-friendly, because the user only has to authenticate once and Kerberos handles the authentication in the background for all servers accessed. Kerberos was developed at MIT, and is widely accepted as one of the most secure ways to perform authentication. However, using tickets is a fundamental change from the more familiar method of requiring a user name and password. It requires modification of both the client software and the server software so that they present and accept tickets, respectively. A service that has been modified to work with Kerberos ticket authentication is said to be Kerberized. If you experience trouble authenticating, it is possible that your site either doesn't implement a Kerberos ticket infrastructure, or that only a few of the most important servers are Kerberized. Working with Kerberos TicketsIf your site is using Mac OS X Server for the directory server, your clients will automatically be using Kerberos when you configure Mac OS X to connect to an Open Directory server, as explained earlier in this lesson. Kerberos can work with other types of servers, such as UNIX or Linux servers, running the standard MIT Kerberos. Such configurations are complex, and often are customized for each individual site. Details of these configurations are beyond the scope of this book. In either case, if your site is configured for Kerberos, your users may use the Kerberos applications on Mac OS X. In a perfect Kerberos configuration, Kerberos is integrated with the login window, and the Kerberos login is not exposed to the user.

The Kerberos tickets are visible in the Kerberos application (/System/Library/ CoreServices). Here are five tasks that you can perform with the Kerberos application:

TIP Because Kerberos tickets remain active for many hours, anyone accessing your computer during that time would have access to the Kerberized services available to you. Take steps to restrict physical access to your computer while you have a valid ticket. Troubleshooting AuthenticationTroubleshooting authentication can be particularly tricky. You can view the ticket using the Kerberos application (/System/Library/ CoreServices) to check whether the ticket has expired. Also, be sure the clocks on your computers are synchronized within five minutes. (Using a network time server is a good idea.) The error and server logs may contain useful information. Error messages in /Library/Logs/DirectoryService.error.log can help identify which plug-in is having problems. To locate the source of an authentication problem, try logging in locally on the server, or from other clients. |