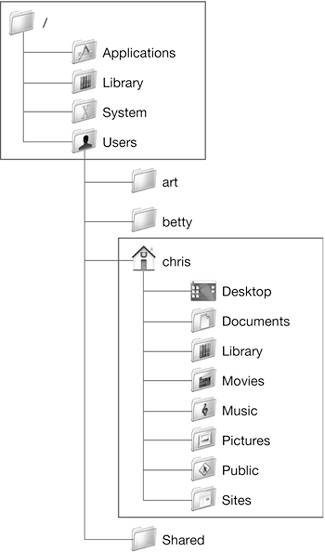

Understanding the File System LayoutAwareness of low-level details of disk drives is helpful for troubleshooting, but most users simply format their drives, install software, and use the computer to do things. The thousands of Mac OS X system files are irrelevant to them, and they do not need to know where the operating system stores files for its own use. Mac OS X shields users from this complexity in several ways. First, while there may be thousands of files installed with the OS, the average user only sees the interpreted view the Finder provides of those files. This includes displaying a user-friendly layout of the file system, despite the fact that the underlying representation is considerably more complicated. Second, the Finder has mechanisms in place to link files with applications that can open them with a double-click. The Finder manages system resources during this process, such as identifying the user's preferred applications for opening particular files, and locating fonts for displaying the information inside a word-processing file. Understanding the Finder's role in simplifying the user's interaction with the file system will help you troubleshoot file system issues. Examining Top-Level and Home FoldersMac OS X permissions distinguish between system files and files that can be configured and modified by users and administrators. This gives greater protection to important system files. Folders are often denoted in terms of the path to their location, which establishes their position in the file system hierarchy relative to /, known as "root" due to its position at the top of the file system hierarchy. (The term root comes from the file system metaphor of an inverted tree, where the root structure is at the top.) A folder called /Applications, for example, is located in the highest level of the file system, and is found in /. A folder called /Applications/Utilities is found in /Applications. The main top-level folders in Mac OS X are Applications, Library, System, and Users. If you have installed the developer tools, you will also have a top-level folder called Developer. If you have installed Classic on the same volume, you will also have the top-level folders Applications (Mac OS 9), Desktop (Mac OS 9), and System Folder.

When you create a user account (see Lesson 3, "User Accounts"), Mac OS X creates a home folder for that user within Users. This location is where that new user stores personal documents. Other users do not have write permissions for your home folder. Items in the active user's home folder are often described with ~/ before the name, because that is how you could identify them at the command line (see Lesson 7, "Command-Line Interface"). By default, the following subfolders appear under each user's home folder:

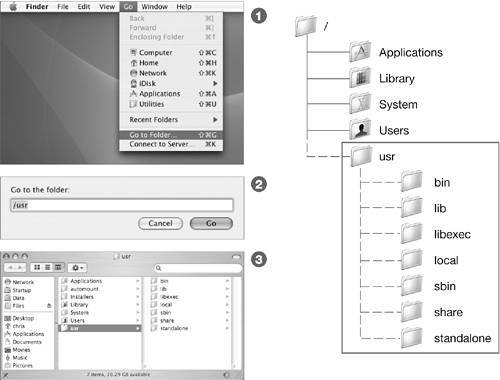

NOTE Mac OS X structures a new user's home folder by duplicating the appropriate language's user template (/System/Library/User Template). With the exception of the ~/Library folder, you needn't keep any of the other home folders if you don't want them. Also, there is nothing that prevents you from placing MP3 music files in the ~/Documents folder, or storing MPEG movies in the ~/Pictures folder. Keep in mind that some applications expect to find documents in specific places, so deleting these folders or placing your documents in other folders may cause problems. In Mac OS X, core operating system files reside in a folder called System. To secure the integrity of the core system against malicious or accidental removal of files, System is marked read-only for all users. Editing system files requires administrator authentication, whether you access the files via the command line or use an administrative utility. NOTE Deleting files from System can cause major problems, some of which may require that you reinstall Mac OS X. End users should be instructed to leave the contents of System undisturbed. System-wide resources that are not installed by the operating system are added to the Library folder. For example, many third-party utilities install startup items in /Library/StartupItems. The Library folder is accessible to administrator users. Administrators should add resources to Library, not to System. Since Mac OS X is a multiuser system, each user has separate resources, such as personal fonts. These resources are stored in each user's home folderspecifically, in the ~/Library folder. For example, the Mail application stores all of a user's mail in the ~/Library folder. This system ensures that user-specific information is stored in each user's home folder, protecting that information from other users, and making it easy to back up and restore all of the documents and preferences for each user. Viewing Hidden FoldersSome folders do not ordinarily appear in the Finder. Most of these folders are used by the system and are not useful to ordinary users. To see these folders in the Finder, you can choose Go > Go to Folder, enter the path, then click Go.

Hidden top-level folders include private, cores, etc, tmp, var, Volumes, bin, dev, sbin, and usr. Permissions for these hidden folders are set to allow only the root user to write to them. An administrator can read the files but cannot make changes without authenticating as root. In addition, any folder or file with a name beginning with a period (.) will not appear in a Finder listing. You can go to a folder with a name beginning with a period if you navigate to it with Go to Folder. You can also use the Finder's Find command to identify invisible files by searching for the invisible attribute. NOTE Files and folders that are hidden in the Finder are visible at the command line, as you will see in Lesson 7, "Command-Line Interface." |