Monitoring Process ManagementA process is a running program or set of threads, and an address space. A thread is a set of instructions that can be assigned independently to the CPU. Therefore, different threads of a single process can run on one processor at different times, or at the same time on different processors. This is called symmetric multi processing. The job of a process is to manage memory and other resources related to the execution of its threads. Processes can run without an explicit user interface: for example, some applications and most system-level processes, called daemons (pronounced "demons"), run in faceless mode. Activity Monitor (/Applications/Utilities) allows you to view and monitor every application and process that is running on the computer. As stated in Lesson 3, "User Accounts," every program (and therefore every process) is owned by a user. Activity Monitor tells you who owns each process, its status, how much of the CPU is being used to run the process, and how much memory is used by the process. You can identify the process by its ID number, which appears in the Process ID column. Each process ID (PID) is unique.

In Activity Monitor, you can sort processes by column heading. Click the column heading to select it, and click it again to sort up or down. You can also filter the process list by choosing which processes to show from the pop-up menu in the Activity Monitor toolbar, or by typing a partial process name into the filter field. Although it might seem easy to match a process to a running application, don't always make that assumption. For instance, if Classic is running, its process is actually called TruBlueEnvironment and all of the applications running in Classic are merely threads of that process. Also, Activity Monitor displays some Carbon applications as LaunchCFMApp, rather than listing their individual application names. To see more information about a process, including memory usage, statistics, and open files, select the process in the Activity Monitor window and click the Inspect icon in the toolbar. To quit a process, select it in the Activity Monitor window and click the Quit Process icon in the toolbar, or choose View > Quit Process. This is just like using kill at the command line. You can also use Force Quit, which is equivalent to the kill command, but with a more abrupt halt of the process (kill-9 at the command line). You will read more about quitting applications in "Troubleshooting Applications in Mac OS X," later in this lesson. The bottom pane of Activity Monitor contains buttons you can click to see system-wide information about the CPU, system memory, disk activity, disk usage, and network statistics. Using Activity Monitor to Force a Process to QuitActivity Monitor is just one of several tools you can use to force quit an application; it's particularly handy for force quitting a process that is running in the background, such as the Dock.

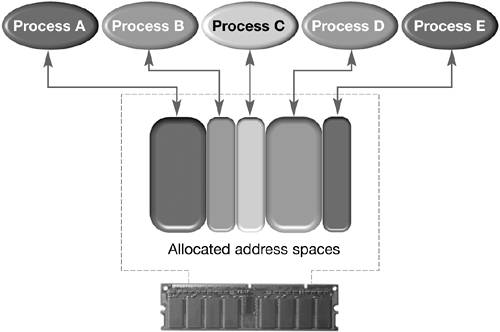

Understanding Protected MemoryProtected memory is a memory scheme in which each process gets its own address space. This memory space is protected because the operating system prevents processes from trying to use memory outside of their allocated space, which is a frequent cause of system crashes on other systems.

The operating system manages the protected memory space of a process. It allocates the amount of memory that processes requests. Practically speaking, the process has a nearly endless amount of memory to work with, but the operating system is really only giving it as much as it needs at any given time. This means that you do not need to assign memory to applications in Mac OS X as you had to in Mac OS 9. Virtual memory uses a swap, or temporary, file on the hard disk to help ensure that there is always enough physical memory for every process running. Data that is stored in RAM but not needed immediately is transferred to the hard disk so that more physical memory can be made available to the next process that needs it. Mac OS X manages virtual memory without the need for user configuration. This also means that users do not need to quit applications when they no longer need them, because inactive applications use little memory and no processor time. Virtual memory can't be turned off in Mac OS X as it could in Mac OS 9; it is always on. Mac OS X 10.4 introduces two new features for virtual memory. The new virtual memory manager uses a 64-bit process model, allowing the operating system to set up an extremely large access space. Users can also enable encrypted virtual memory so that their on-disk virtual memory partition is secure. To do so, open Security preferences and select the "Use secure virtual memory" checkbox. |